System Design Guide: Scalable Job Schedulers & Cluster Management

Design a cloud service where users can execute arbitrary jobs on a recurring schedule or manually.

Functional Requirements

- Users should be able to create/read/update/delete jobs and schedules

- A job is any arbitrary program/computation that a user writes. For example, I could write a program in Python that does

print("Hello World!"), or you could write one that downloads a file and uploads it into a blob storage service. - Ideally we support all languages, but if you can’t think of some way to support them all, let’s just focus on scripts or binaries to start.

- How would you support all different types of artifacts and languages?

- The maximum size of a job (in whatever format they upload) will be 10 MB.

- We maintain the execution history of jobs for 5 years.

- Users can see the status of jobs’ executions both present and historical. For example, they can see whether a job was successful, failed, running, or pending.

- Users should be able to run jobs as one-offs.

- Schedules should have a maximum granularity of a year and a minimum granularity at minute.

- Security & Isolation: We should protect customers’ jobs from interfering with other customers’ jobs (both in terms of resource contention and possibly malicious activity).

Non-functional Requirements

- We run 100M jobs a day (80% of jobs are from schedules, 20% of jobs are from one-offs).

- We have 100k customers spread evenly across 10 regions.

- It should take at most a few seconds to schedule a job (stretch goal: <100 ms).

- A job can run at most for 24 hours, after this we’ll cancel the job and tell the user that the job was timed out.

- Users’ jobs should not impact one another (in terms of performance, security, correctness, etc.)

- The load of the system can vary over time depending on the fluctuation of jobs. I.e., depending on the types of jobs ran, they may only be ran on weekends or weekdays.

- The system is 99.9% available.

- The average job runs for 1 minute.

- There are 200M schedules defined in the system and 200M unique jobs defined in the system.

Back of Envelope Calculations

- The system averages 100M jobs in day. 86400 seconds in a day = ~1157 jobs per second. Since the average job runs for 1 minute, we would have ~69420 concurrent jobs running at any point in time.

- This means we’ll have to think carefully about how we autoscale the fleet executing the jobs and consider peaks in usage.

- If we assume there are 200M unique jobs defined in the system with a maximum size of 10 MB = 2 PB of data to be stored.

Key Components

- User Interfaces (Console/CLI): Front end tools where users can create, manage, and monitor their jobs.

- API Layer: Handles incoming requests from users. Allows users to create, update, and delete jobs, as well as view job status and history. Performs AuthN/Z.

- Scheduler: Responsible for triggering jobs based on their defined schedules.

- Job Queue: A message queue system that holds jobs waiting to be executed.

- Job Workers: Scalable compute resources that execute the jobs.

- Fast autoscaling and dynamic capacity prediction.

- Database: Stores job definitions, schedules, user information, and execution history.

- Logging, Monitoring, Metrics: Collects logs and metrics from all components for troubleshooting and performance monitoring.

Data Models and APIs

- Jobs (id, name, binary|script location (e.g., in S3) or containerImage (e.g., in ECR))

- Job Instance (id, status=[completed, running, failed], startTime, endTime)

- Schedules (id, name, jobId, cronExpression)

- Create/Read/Update/Delete APIs for Jobs/Schedules.

- Read APIs for job execution history from job instances.

This is just a sample of what you could come up with. For example, we could also put the cron expression directly on the job object if we don’t want to have schedules to be managed on their own and/or have multiple schedules associated to a particular job.

High Level Design

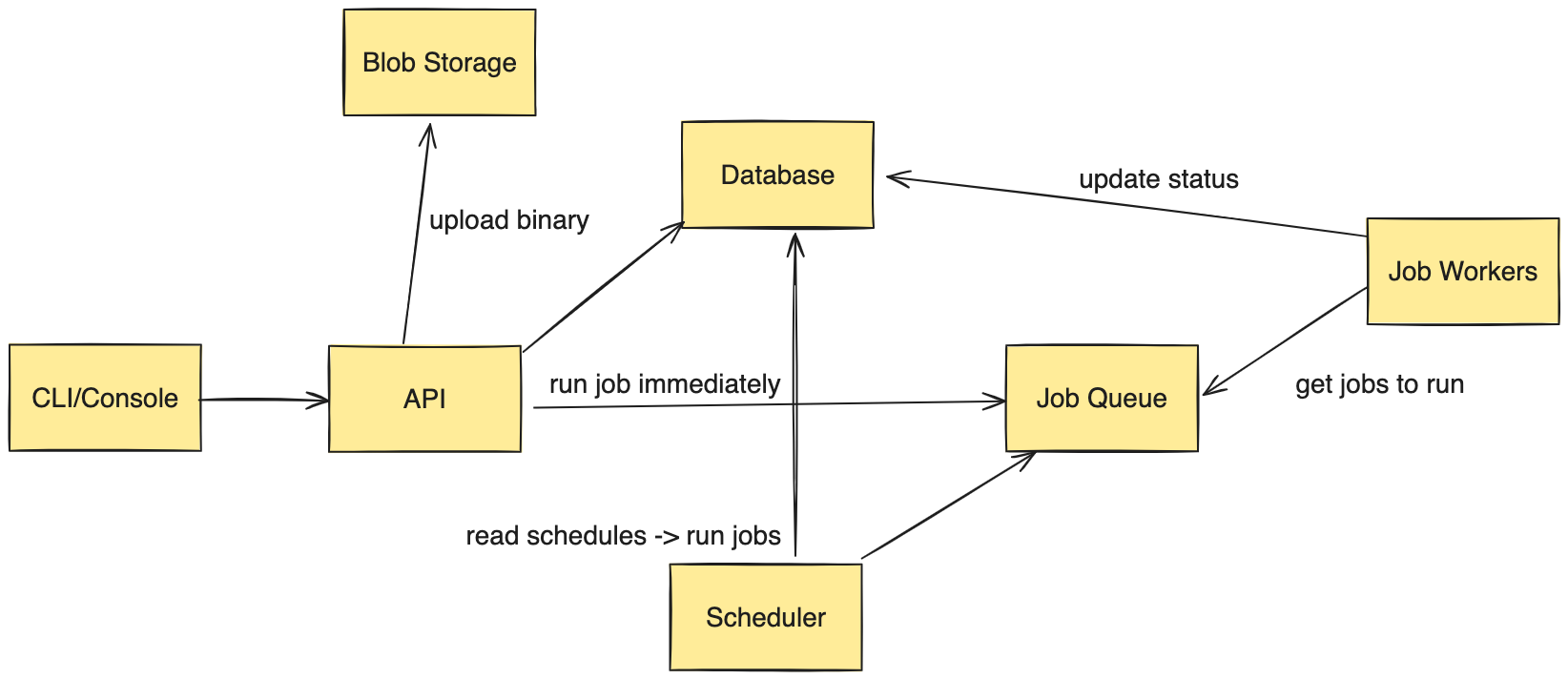

Figure 1: High-level architecture of a scalable job scheduler and cluster management system. This diagram illustrates the flow from user interaction through job execution and status reporting.

Figure 1: High-level architecture of a scalable job scheduler and cluster management system. This diagram illustrates the flow from user interaction through job execution and status reporting.

- Users create/manage their jobs and schedules via a CLI or console.

- Programs are uploaded into a Blob Storage like Amazon S3 or Azure Blob. We store the schedule/job metadata in a database.

- If a user tells us to execute a job immediately, we fetch the information from the database, put it into a queue, and workers execute the job off the queue.

- We have a scheduler that is constantly polling the database and comparing the physical wall clock to see whether the schedule is able to be ran. If it is, we put it in a queue, mark the schedule as being processed, and wait for a job worker to execute it.

- Job workers are constantly polling the queue when they do not have a job / work to complete. Once they pick up a job, they run it, and upload results/job status into the database.

Low Level Design & Deep Dive

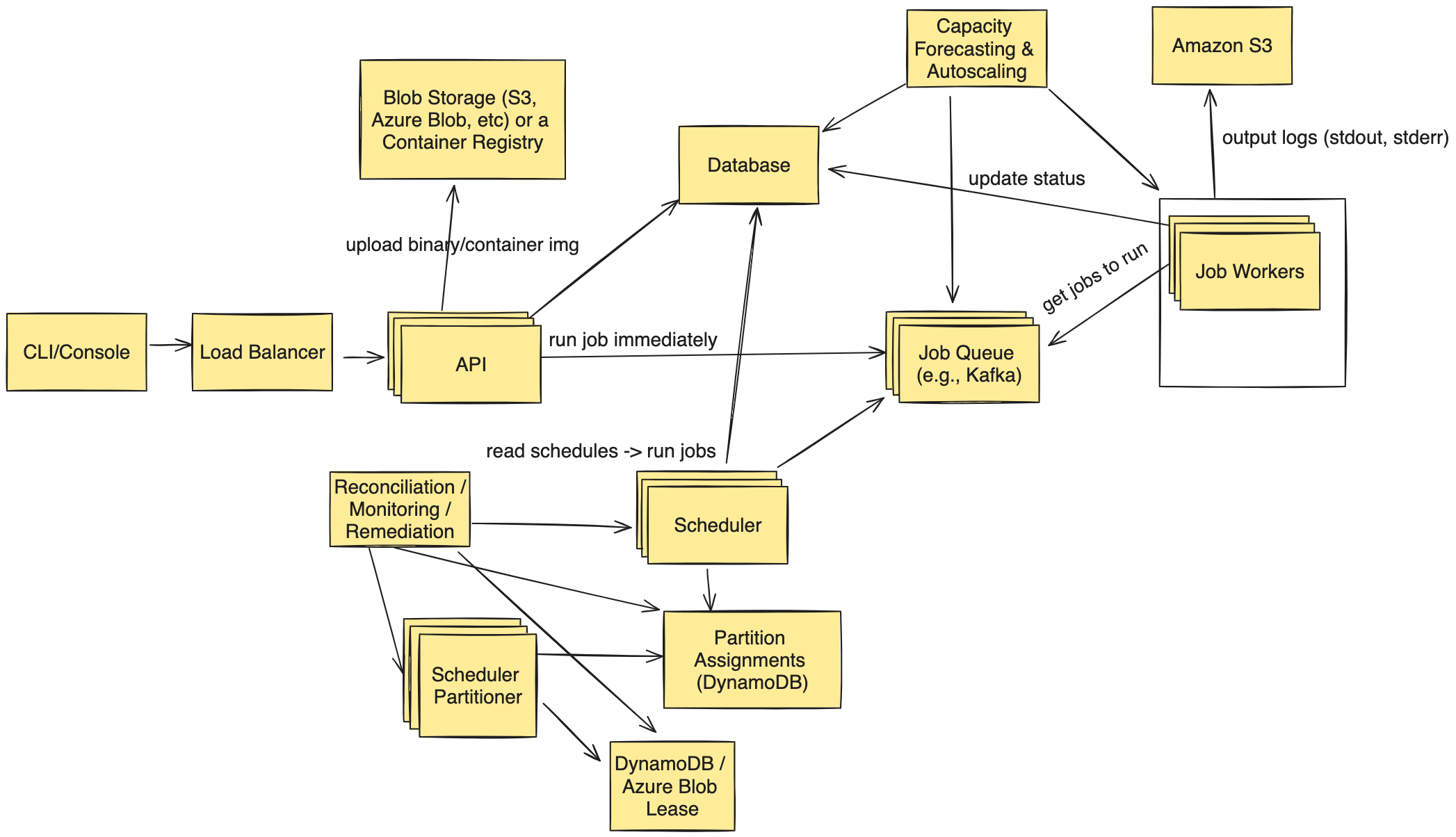

Figure 2: Detailed low-level architecture of the job scheduler system, showcasing key components such as the scheduler partitioner, job queue, and worker fleet. This diagram demonstrates how the system handles job distribution and execution at scale.

Figure 2: Detailed low-level architecture of the job scheduler system, showcasing key components such as the scheduler partitioner, job queue, and worker fleet. This diagram demonstrates how the system handles job distribution and execution at scale.

- Why not have the API directly send jobs to the Job Workers or have the scheduler directly send jobs to the Job Workers?

- We prefer using a job queue as an intermediate storage layer between the API/Scheduler and the job workers to help with back pressure in the system. Without the queue, if there is no worker available to pick up the job, then the API would have to return an error back to the client to try again and the scheduler would have to retry as well. Moreover, if we were to push jobs directly to workers rather than the queue, we would need to have a load balancer of some sort in between that knows how to distribute jobs only to workers that are not currently running jobs. This means the load balancer would have to be constantly polling and maintaining a map of a large fleet (~100k instances, and growing each year as the service scales).

- How do we minimize the latency of the scheduler (i.e. if polling, how to make it fast in a matter of milliseconds)?

- There are multiple ways to do this, but all forms involve some aspect of partitioning. For example, we could partition the database and schedulers associated to each so that each scheduler only has to perform a regular scan over a subset of the database. We could partition based on jobId or customerId. If we partition by customerId, if the partition goes down, it would mean the entire customer is down, so we may prefer to do it simply jobId. We could calculate each job’s run frequency and how long it takes to run to form a “weight” in the system, and run a bin-packing algorithm to form partitions by putting jobs of high weight with jobs of lower weight to avoid hot partitions.

- In this diagram, the scheduler partitioner would be responsible for forming the partitions of jobs and assigning them to schedulers. There is also a fleet of scheduler partitioners, but only one “leader” partitioner running at any point in time; we can use a lease mechanism to establish who the leader is and prevent other partitioners from conflicting. If the leader were to lose control of the lease, another partitioner would take over and become the new leader.

- Once a scheduler is assigned a partition, it can pull all the records from the database in memory and perform in-memory evaluations which will provide better performance than database lookups.

- How do we store jobs?

- If jobs are just binaries, we can upload them to a blob storage like Amazon S3 or Azure Blob. An alternative to this is they could be a container image and they could go into a container registry, which the job workers pull from.

- How do we ensure isolation and security when running jobs?

- A simple and effective way to start out is to make each worker a virtual machine and only run one job at a time. Once the job worker completes its job, we can recycle and re-image the job worker’s virtual machine. We could also discuss more advanced isolation techniques such as a MicroVM like Firecracker.

- How do we minimize latency from workers picking up jobs?

- There are two sources of traffic in this system: 1/ schedules; 2/ one-off jobs. Because we know when all the schedules ahead of time, we can proactively create instances right before a schedule is about to run and have them waiting for work to arrive. We could have a dedicated set of queues/topics for schedules and ensure 100% hit rate this way so long as we always calculate the schedules and bring up the compute in advance fast enough. To handle the one-off jobs, we can keep a running history of all jobs ran in the system. Over time, we can perform historical capacity forecasting to predict how many jobs are likely to run at any time throughout the year in the system and proactively keep a fleet of instances around for this. On top of this, we can have an autoscaling mechanism surrounding the job queue; if jobs ever start to back up in the queue, we know we are not draining the queue quickly enough and need more instances.

- We can bake in some margin to keep good SLAs up, at the expense of our utilization.

- Resources: some jobs may only be scheduled on systems which have certain resources. E.g. some will require large amounts of memory, or fast local disk, or fast network access. Allocating these efficiently is tricky.

- If we provide users the ability to specify the exact hardware they want, then it means we are going to always be stuck offering that hardware. Many systems provide users the concept of an abstract scaling unit like a resource unit which may involve vCPUs, memory, etc. We can provide users the ability to request these job scheduling resource units and offer fractions of our virtual machines to them in an isolated way.

- Operations: how to make sure our service is always available?

- All of our components are backed by multiple instances and we have a means to failover them quickly if one instance encounters an issue. We’ll provide alarms/dashboards/metrics/logs on all components.

Additional Topics and Considerations

- If we can pack multiple jobs (e.g., if we could trust all actors in the system like an internal company) onto a single VM, then our scheduler can employ weighted decisions based on job similarities and historical data, enabling accurate estimation of resource needs and job durations.

- When we rollout software upgrades, we have to be careful to prevent disruption to jobs. E.g., we can do this in a blue/green manner where we only patch hosts when they are not running a job. We always ensure we have the proper amount of capacity overhead based on how quickly we are patching (e.g., if we patch 20% of the fleet, we need 20% more hosts) - we will always go above 100% of the expected fleet capacity.

- We could consider support for task priorities.

- To avoid cold starts, many systems offer a “provisioned” or “allocated” mode where the code is always running on a certain number of machines. We could offer this at a premium for users and have different billing models. E.g., for provisioned instances users would pay per second constantly rather than only for the amount of time it takes to run their job.

- Task startup time is often consumed (>80%) by package installation times. Systems are working around these limitations using Torrent-style protocols and concepts like Erasure Coding.

- We can use cells to affect isolation (security, reduce blast radius of deployments, and group jobs in different ways).

- Security & Performance Isolation via sandboxes (chroot, cgroups, namespaces, independent isolated kernels, (micro)virtualization technologies like Firecracker)

- Cancellation - users may want to kill a long running job, or prevent one from running.

- Dependencies - some jobs may only be runnable once other jobs have completed, and thus can not be scheduled before a given time.

- Deadlines - some jobs need to be completed by a given time. (or at least be started by a given time.)

- Permissions - some users may only be able to submit jobs to certain resource groups, or with certain properties, or a certain number of jobs, etc.

- Quotas - some systems give users a specified amount of system time, and running a job subtracts from that.

- Suspension - some systems allow jobs to be check-pointed and suspended and the resumed later.

Calibration Guide

Put a checkbox or X to indicate whether you met or surpassed the criteria.

- Removes ambiguity in the problem statement

- Drives the conversation

- Can articulate shortcomings and tradeoffs with different designs

- Translates requirements into user stories

- APIs covering requirements

- Sufficient HTTP knowledge/Front End depth

- Familiarity with LBs, app fleets (no single points of failure)

- Familiarity with data layer

- Logging/Tracing/Monitoring

- Proper data models representing schedules/jobs

- Defines how to upload/structure a job (binaries, scripts, or containers)

- Cron or similar expression format for schedule definition

- Sharding support for scheduler and database

- Meets latency requirements

- Caching support

Relevant Papers

Much of this article is based on real-world systems and classical research that can be found throughout the following papers:

- Apollo: Scalable and Coordinated Scheduling for Cloud-Scale Computing by Boutin, Microsoft Research et al

- Mesos: A Platform for Fine-Grained Resource Sharing in the Data Center by Hindman, et al

- Hawk: Hybrid Datacenter Scheduling by Delgado, et al

- Apache Hadoop YARN: Yet Another Resource Negotiator by Vavilapallih, et al

- Tarcil: reconciling scheduling speed and quality in large shared clusters by Delimitrou, et al

- Large-scale cluster management at Google with Borg by Verma, et al

- Container Loading in AWS Lambda by Marc Brooker

- Quincy: Fair Scheduling for Distributed Computing Clusters by Isgard, et al

- Mercury: Hybrid Centralized and Distributed Scheduling in Large Shared Clusters by Karanasos, et al

- Sparrow: distributed, low latency scheduling by Ousterhout et al

Related Posts

Thanks for reading this far. Be sure to check out all of my related technical interview practice posts:

- System Design Interview Framework & Strategy

- Behavioral Interview Framework & Strategy

- Coding Interview Framework & Strategy

- Technical Program Management (TPM) Example Interview Questions